Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

- W. B. Yeats, The Second Coming

Welcome to Restoration. This is a forum to share ideas on repairing our society’s broken institutions. We don’t propose to know everything. But even we lay people, we ordinary citizens, can agree that institutions and structures within our communities have undergone great harm and need to be restored.

Our society’s contemporary outline first emerged in “the West,” but has spread around the globe. Its inheritance springs from a peculiar confluence of habits and customs that had been practiced for centuries before anyone branded them as “ideas.” Among these notions are the rule of law, the tradition of liberty, the system of representative government, a toleration of difference, and a commitment to pluralism. Each of these ideas might have been extinguished in their infancy, but for the grace of God and the force of their appeal.

Today, this inheritance is at risk of a breakdown from a variety of pressures. In every Western nation, these ideas are in rapid retreat. Social decline is pervasive: institutions no longer function properly; leaders and experts aren’t trusted. People are less hopeful, more anxious, and more resentful of each other than ever before. The Law no longer even aims at the equality of all people, but advances the privileges of certain groups to the detriment of others. Western society, for all its prosperity, seems in most domains to be in a process of pervasive devolution. Its people are demoralized. It shows all the signs of a society subverted.

For a time, many spectators refused to believe that anything was seriously wrong. The tide of populism was, they told us, a momentary manifestation of frustration. The decline of each of our institutions was viewed in isolation, as merely a problem of poorly selected leadership which could be corrected after the next election. The sense of hopelessness that people felt was explained away as the temporary consequence of the rapid transition away from industrialism. In this light, though there were problems, they were distinct from each other and would be corrected in time.

No serious person believes this now.

It is obvious to everyone that something is seriously wrong in Western society. People are encountering this crisis in different ways, though a compelling explanation remains elusive. Let alone a solution. I am reminded of the Buddhist parable of the blind men and the elephant. The story goes that a group of blind men, who have never encountered an elephant before, hears that one has been brought to their town. They go so that they might touch the elephant and consider what it might look like. One man touches the elephant’s trunk and thinks it must be like a large snake. Another touches its leg and likens it to a tree. A third who grasps the elephant’s tail says it feels like a rope. A fourth presses its sides, and when it does not budge, compares it to a wall. The fifth touches its tusk and thinks it to be like a spear.

In all, several blind men touch the same elephant and come up with different explanations. Although there is truth in each of their assessments, none are able fully to comprehend the elephant in its totality. Those who feel the decline in Western society are like these blind men, encountering the elephant in their own ways and grasping at explanations in the half-light of dusk.

When the omni-breakdown burst forth in 2020 with the crises of the George Floyd riots, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the draconian controls that governments imposed, most of us awoke from our dogmatic slumbers and behaved like the blind men, ping-ponging around theories with the tremulous (sometimes furious) chatter that heralds the turning of an age. An age of anxiety.

As one of those blind men—perhaps I am just coming across one part of the elephant—my perception is that we are a society subverted. By this, I do not mean that we are subverted in the dictionary sense, or in the sense connoted in spy novels. I mean we are subverted in a more systematic and totalizing way.

Lately, I’ve been compelled by the theory of Soviet subversion described by Yuri Bezmenov. A friend pointed me to a recording of a lecture he gave in 1983 on Soviet methods for psychological warfare subversion. I encourage all of you to listen.

Bezmenov had been a KGB agent promoting foreign subversion when he grew disillusioned with the Soviet system and defected to the West. In 1970, Bezmenov fled to Greece, then Canada. He dedicated the rest of his life to exposing the secret Soviet apparatus of subversion in the West.

This kind of subversion is familiar to me because of my background. I come from Africa, where many countries were subverted by the USSR. The societies of many were totally warped by Soviet infiltration. They never recovered.

One of the key insights Bezmenov expresses about a subverted society is that, for a while, there is only a sense that something is wrong. A mood. A “vibe.”

Until, finally, revolution sputters into view. The pressure makes society rumble like a volcano, quiet one minute and flaring the next, but, overall, it builds ominously.

Though our present discontents may seem to many as a surprise, especially when compared to the confidence and exuberance of the West after the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s and into the 2000s, the origins of some of the phenomena we are seeing today may have their roots in the late 50’s and 60’s.

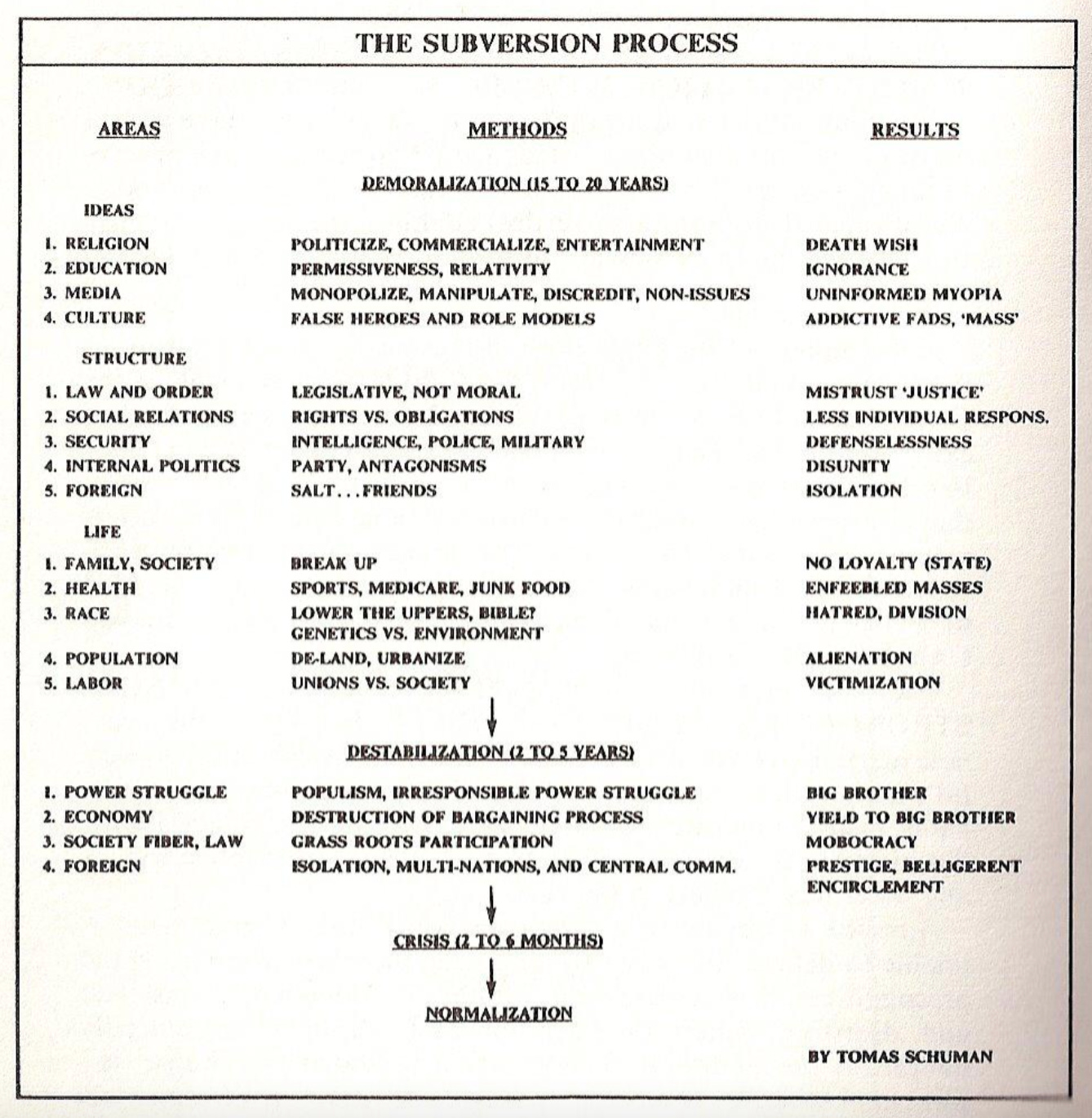

Bezmenov described the subversion process as a complex model with four successive stages, a diagram of which I have provided below. These are, in order: demoralization, destabilization, crisis, and normalization.

Demoralization is the first stage and requires the subverter’s greatest investment of time and resources. Bezmenov claims the process of demoralization can take between 15 to 20 years, because that is the amount of time it takes to educate a new generation.

The demoralization process targets three areas of society: its ideas, its structures, and its social institutions. The targeted ideas include religion, education, media, and culture.

For religion, demoralization involves the politicization, commercialization, and transformation of faith into a source of entertainment. This leads to a “death wish,” by which Bezmenov means that the afflicted would embrace self-destructive behaviors and ideas. Thus, all moral constraints can be eschewed in the pursuit of “just” and “virtuous” causes, and in subsequently inevitable radical action.

What else could explain the near-daily moral panic attacks masquerading as righteous activism, from the destruction of artwork to self-immolation? As human life ceases to look inviolable, we might also expect measures like euthanasia to gain steam, not just to help end terminal anguish, but to end all manner of non-debilitating hardship. No surprise, then, that we are seeing movements speeding ahead for “assisted dying” in the US, UK, France, Ireland, and the rest of the West.

The next targeted area is the fundamental structures of society. These include the rule of law, social relations, security, and internal and external politics. For example, demoralization in the rule of law would entail undermining our trust in legal institutions and eroding the basis for legal authority. This could be accomplished by presenting the justice system as corrupt or illegitimate and by sowing distrust in the mechanisms of law enforcement. As a consequence, citizens lose confidence in the administration of justice, paving the way for untold social disorders, including legal nihilism, where people disregard the law en masse. In America in 2019, 12 unarmed black men were shot by police, most, apparently, in self-defense. Most Americans who described themselves as “very liberal” estimated the number at 1000 or more. A fifth thought 10,000 or more. Were the George Floyd riots, then, any surprise? Conservatives are losing their confidence in law enforcement too, in part because of the indulgent treatment they observe the law taking towards Antifa, BLM, and pro-Palestinian rioting. Both sides agree: there is a two-tiered police and justice system.

The third area, “life,” includes core social institutions such as family, health, race, population, and labor. Demoralization of the family is probably a familiar concept to us all. It involves promoting ideas that weaken the bonds between members of the family, promoting narcissistic individualism over family unity, creating financial stressors that discourage family formation, and undermining parental authority. The result is that, not only do individuals feel less attachment to family, the fundamental unit of a healthy civilization, but they even end up detached from society itself. As we now know, the breakdown of family is strongly correlated with the epidemic of mental health crisis and explosive rise in violent crime. 85% of American youths in prison come from fatherless homes.

It isn’t hard to imagine the mechanisms for demoralization in the areas I haven’t discussed. The point of demoralization is gradually to degrade the foundations of a healthy society across all domains and to encourage sickly attitudes to fester in their place.

The demoralization process also exploits preexisting discontents within and between communities, seeking to widen them. In British society, subverters embed within republican movements to destabilize the constitutional architecture of the state. Throughout Europe, the disaffected and numerically significant Muslim minorities may have been an easy target for subversion by Islamists schooled in the art of Soviet tactics. I will say more on that in a future post.

In American society, subverters infiltrate minority groups like BLM and seek to exploit the Civil Rights mindset. Even putatively new divides, such as with transgenderism, can be interpreted through this lens. What a society used to call abnormal and pathological, subversion normalizes.

It can even be seen when it comes to pedophiles, now rebranded as “Minor Attracted People.” By hijacking the inheritance of the Civil Rights movement, nearly any “marginalized” group has a vehicle to try to “mainstream” deviant behavior.

Another striking feature of the demoralization process is that it’s usually perfectly legal. Subversion abuses the tolerance of an open culture, forcing the host society to accomplish its aims like a virus does. According to Bezmenov, a successful subverter could come to be employed by a major university and teach a class on communism. While spectators might get irritated, simply asking whether such a subject should be taught gets you labeled as a crank. “Who are you to decide what can’t be taught?” The subverter, meanwhile, works to indoctrinate more minds and to secure positions for more subverters or useful ideologues. If you oppose this, you are asked “What do you have against intellectual diversity?” Once the subverters come to dominate an institution, they can apply institutional pressure. Curbs on academic freedom, the curriculum, and the hiring process inevitably follow. Repeat ad infinitum.

Even in the cases where subversive activity is clearly illegal, such as with the George Floyd riots and many anti-Israeli protests today, the crimes committed are presented as righteous, so it is difficult for the public to countenance the idea that the chaos should be stopped forcefully.

Destabilization is the next phase. This process is considerably shorter, taking anywhere between two and five years. With demoralization now reaching its full maturity, society is increasingly paralyzed by harsh domestic turmoil across all sectors. Democratic politics take on the character of a vicious struggle for power. Factionalism takes hold. Economic relations degrade and collapse, obliterating the basis for bargaining. The social fabric frays, leading to mob rule. Society turns inward, leading to fear, isolationism, and the decline of the nation-state itself.

It is important to understand that, at this stage, the process of subversion is largely self-propelled. What once required active involvement on the part of a foreign subverter has now taken root and grows organically. Then, society ruptures all at once in a rolling series of crises as the full extent of the cancer manifests. This stage takes, in his estimation, only two to six months.

Finally, says Bezmenov, society enters the normalization stage, which is when the subversive regime takes over, installing its ideology as the law of the land. The enemy has totally conquered the target society without ever firing a shot.

This is what true Soviet-style subversion looks like. This is what happened to the African, Asian, and Latin American countries in the Soviet sphere. It is why they remain shattered to this day.

Subversion in the West caught many, including myself, by total surprise. The polarization we struggle with is intentional, not merely a byproduct of differing beliefs. Even within factions, there is increasing fragmentation.

We need a deliberate effort to mobilize against this subversion. I fear that if we do not take action soon, what happened in Africa may be what happens to the countries of the West within the next generation.

Once I heard Bezmenov’s lecture, some of the seemingly topsy-turvy developments in our institutions fell into place. I am not saying that Bezmenov’s lecture explains everything. It clearly cannot single-handedly address all the West’s problems. But things like the widespread acquisition of useless, aggressively ideological degrees in gender and race, or the claims of the possibility of an unlimited number of genders, or the total racialization and “decolonization” of our political discourse, or the demands to defund the police, the toppling of statues, the defacing of art, the “spontaneous” protests to dismantle our structures, and much else—these do come across as acts of subversion, rather than mere expressions of discontent or youthful energy run amok.

Subversion is a risk to all open societies. As Bezmenov says, subversion is a two-way street. A closed society is immune to subversion because it simply tells potential subverters to leave. Free and open societies cannot rely on this defense. They are, in a way, too tolerant.

During the Cold War, the United States was able to forestall subversion because its institutions and people had the necessary antibodies to stave off subversive ideas. Doing so is easier when you have a visible peer as an enemy. But when the Cold War came to an end and we declared victory, we mistakenly thought our enemies stopped, and so we let our guard down. Perhaps the subversive investment made in the US during the Soviet era is now paying off. It is even possible that new enemies, from Russia, to Iran and China are using these Soviet techniques to destabilize the US. Fortunately, we are waking up and acknowledging that something is off.

America has, in my view, reacted to subversion in a healthy way. Everyone is scrambling to figure out what is going on. In response to the corruption of every major institution, we are turning to our greatest asset: the market. It is easy to speak in austere, abstract terms about the significance of the market. But it’s more than just a vehicle for efficiently distributing goods and services. It is the sum total of relations in a free society. When the press, the doctors, and the schools fail us, free economic and intellectual structures allow us to create our own institutions.

I also see our technological advancement as an asset. I know many of my friends are deeply worried about the potential for technology to ruin us. Certainly, tech is used to disrupt and, in many ways, to propel us downwards; but it is a mistake, in this case, to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

We’re seeing this combination of the market and technology now with the course correction in the media. Americans are turning in droves to alternative media sources outside the stale institutional organizations that have been subverted or have self-subverted. This project is intended to be an addition to the growing chorus of voices using independent platforms like Bari Weiss’ Free Press, working to diagnose and solve today’s existential crisis.

If I’m right about the relevance of subversion, then one logical response is to invert Bezmenov’s table. If the problem is demoralization, the answer is to remoralize. We must find and restore the moral fiber and foundational principles of the West.

The countries of the West are indeed demoralized, with perhaps the sole (but ailing) exception of America. In this remoralization, it is critical to find unity—to find authentic and incisive leaders in religion, education, the media, and so on. We must not only find these leaders, but bring them together. If I am correct, then these individuals are all running up against different parts of the elephant, and we can only defeat our enemies by coming together. This is what Restoration is all about; these are the people for whom we are writing.

With this inaugural post, I want Restoration to be a tool to gather all the other blind men together. As we continue to discover more and more brokenness, we need to start mending. The goal of this project is ultimately the restoration of unity. To that end, we will host conversations between religion and science, educators and parents, employers and employees, all in a bid to find common ground. We want to answer such questions as: why does family matter, why are borders and citizenship important, and why do nations matter? Because subversion has been a multi-decade project, so too will this restoration require decades of deliberate work. Restoration is a commitment to the lessons of the past, the struggle of the present, and the dawn of a new age that must be our own creation.

Half a century ago, as a child, I moved to New York from behind the Iron Curtain. (Translation for American youngsters: the land behind the Iron Curtain was a collection of police states ruled by the Soviet Union, which is what we used to call communist Russia when it pretended not to be an expansionist empire.) It was a wonderful time in America, where my generation enjoyed the luxury of believing that the threat of communism was a silly bit of paranoid propaganda. The McCarthy era was long over and forgotten, antisemitism was a thing of the past, and nobody had time to remember how many of the black listed just happened to have been Jews.

I was ecstatic to find myself in such a free society and I fit in immediately. Except...occasionally, when I mentioned in passing to my free-thinking friends that, actually, it wasn't completely crazy to worry about the Soviet threat, where, as it happened, school children were indeed taught that communism was destined to spread to the whole world.

I soon learned to turn a blind eye to my own worries.

It is sobering to realize now how many warnings we all learned to ignore. Life becomes too heavy when every warning must be heeded. If we want to understand how a society can be gently herded to disaster, we might remember that our need for optimism and hope is so powerful that it can blind us to the most glaring forms of evidence.

Ayaan, it’s so great to have you here on Substack! You have always been a voice for what is decent, true and best in people. Your commitments and purpose are a fit for this place. In any case Substack is more than technology; it is incubation and sustenance for people engaged in finding or making the path forward.

The challenge of restoration must include institution building. You make that goal clear above. But it also must include the invention of new language for describing the world and the future, a language that calls forth what is best and highest in human beings, and that speaks to both rising and passing generations. The best example most Americans have of such an invention – in living memory for some - is probably the visionary and aspirational poetry of the civil rights movement. It is confusing to call it poetry, because it's not about poems, but poetry it is. Its next incarnation will come forth if we work and strive and listen to bring it forth. This is one of the places where that can begin to happen. As I wrote above, Substack is more than just technology. It’s one place where people who continue to love the world in spite of everything can strive to remember and say what the world can still become.