Political Gender Polarization Among Young People

What’s Driving the Sexes Apart?

Across most of the developed world, the political attitudes and voting behavior of young women have moved well to the left of young men over the last decade. Young women are becoming increasingly progressive while young men either stand still or move to the right, including the populist right. In this post I want to address two questions about the ideological and partisan polarization in Gen Z: What is the magnitude of the gap, and what is causing it? In my next post I’ll address two other issues: What are its likely effects, and what if anything can be done to reverse it?

The Growth of the Political Gender Gap

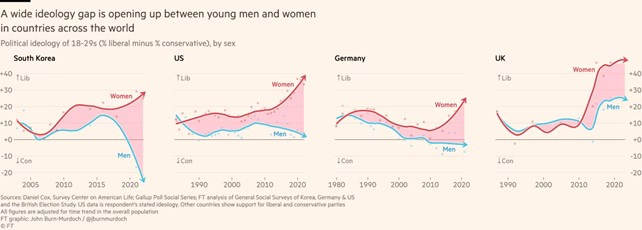

Let’s start with the degree of polarization. Using Gallup data on ideological self-identification for the US, the Financial Times recently found that, after decades where the sexes were roughly equally liberal and conservative, women aged 18 to 30 are now 30 percentage points more liberal than their male contemporaries. This gap has opened in just the last ten years.

Intentions to vote for left- and right-wing parties painted a similar picture in the UK, where young women are now more left-wing than young men by a 25-point margin, and in Germany, where the gap is 30 percentage points. In South Korea it is not so much a gap as a chasm. Young women are about 50 points more liberal in their voting intentions than their male counterparts, as you can see below.

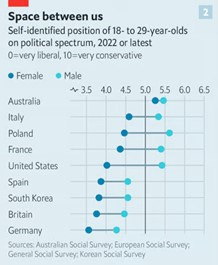

The Economist picked up the same picture of ideological polarization along gender lines when it analyzed survey data from 20 developed countries. As you can see below, two decades ago there was little difference between men and women aged 18-29 on a self-reported scale of 1-10, from very liberal to very conservative. But after 2014, the gap widened considerably. By 2020, young men were only two percentage points more likely to describe themselves as liberal than conservative, whereas among young women, this had widened to a massive 27 percentage points.

The pattern was also rather uniform. In all the large countries they examined, as you can see in the next graphic, young men were more conservative than young women.

The gap is visible in voting behavior as well as in ideological self-identification.

In South Korea’s 2022 presidential election, for example, older men and women voted similarly, whereas young men swung heavily behind an overtly anti-feminist president, Yoon Suk Yeol of the People’s Power Party, who attracted the votes of more than 58% of men in their 20s. Women in their 20s, by contrast, backed his rival from the left-wing Democratic party in equal and opposite numbers.

In Europe, young male votes helped fuel the rise of populist right parties in EU elections that I wrote about in a previous post. In almost every major country, young women were more likely to support left-wing parties and young men to favor the right or the radical right. In Belgium, for example, nearly 32% of young men said that they supported the populist-right Flemish Interest party, compared to only 9% of women in that age bracket. In Germany, 18.2% of young men favored the Alternative for Germany compared to 10.2% of young women. The only exception was France, where the National Rally was equally popular (32% of the youth vote) with both sexes.

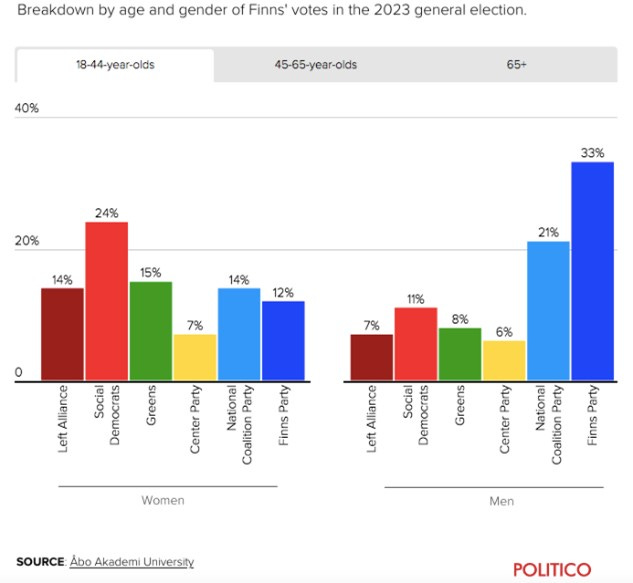

A similar picture emerges in recent European national elections. Consider the 2023 Polish election. The top choice for 18- to 29-year-old men was Confederation, a party that combines laissez faire economics and conservative social values, which was backed by 26% of young men, compared to just 6% of their female peers. In Finland’s last general election, also in 2023, young women,far more than older ones, favored parties such as the Left Alliance and the Greens. But the populist-right Finns Party performed miles ahead of other parties among young men, as you can see below.

As for the US, a poll from this spring found that among 18 to 29-year-olds, President Biden’s lead with women stood at 33 points in contrast to a mere six points among young men. This is a big shift from the same stage of the 2020 campaign, when Biden’s lead among young women was nearly identical (+35), while his lead with young men stood at +26. This demographic is notoriously difficult to poll, so treat these numbers with some caution. Still, the rightwards shift among American young men is unmistakable. It lies behind the huge rise in support for Donald Trump among young people (+40 since February 2021!) picked up in an Economist/YouGov survey from around the same time.

The growing partisan gender divide among young people is also evident in their social attitudes more broadly, especially towards each other. A survey by Glocalities between 2014 and 2023 found that young women have embraced “anti-patriarchal” values over the last decade and are now most concerned about issues such as “sexual harassment, domestic violence, child abuse and neglect, and mental health problems.” Men by contrast were generally more focused on “competition, bravery, and honor.” The study found young men have become more “patriarchal”—skeptical of feminism—in their orientations overall when compared with women and older men.

This matches findings from the Survey Center on American Life, which discovered that young women are much more likely to identify themselves as “feminists” than young men. Only 43% of Gen Z men identify in this way, much less than Millennial men, compared to 61% of Gen Z women and 54% of Millennial women. The study also found a growth in the proportion of young men who say they are facing discrimination over the past four years. Nearly half of all men aged 18 to 29 said they felt this way, the highest of all male age groups surveyed.

We see a similar trend in Europe. According to a study from Gothenburg University, when people in 27 European countries were asked whether they agreed that “advancing women’s and girls’ rights has gone too far because it threatens men’s and boys’ opportunities”, young men were the most likely to agree, as you can see below. Contrary to widespread assumptions about the political life-cycle, they are now to the cultural right of older men in their views of feminism.

What is Driving This?

It is complicated, but five causes of youth gender polarization stand out: the feminization of left-wing politics since #MeToo, the sex gap in higher education, female hypergamy in the dating market, the rise of social media echo chambers, and the paradoxical increase in personality profile differences between the sexes under more gender egalitarian social conditions. Let us look at each in turn.

Feminized Leftism

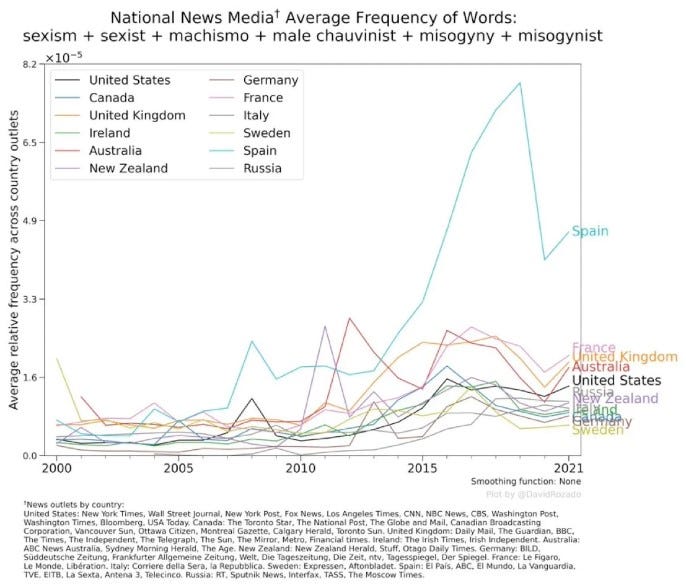

The #MeToo movement appears to have been a key trigger, giving rise to a shift towards feminist values among young women after its eruption in 2017. The gender gap in the US first passed 10 points that year. You can see how the media helped to ramp up coverage of sexism and misogyny around this time in David Rozado’s data below. The conjunction of the two appears to have pushed a younger generation of women to the left as they entered adulthood. The issue of abortion became more salient still after Roe was overturned in 2022.

For this cohort of young women, equal access to employment and education is not enough. A new litany of issues has roused them: sexual harassment, restrictions on abortion, the post-pregnancy gender pay gap, and the allocation of childcare responsibilities, in particular. The political left has done a good job of persuading women that these are all burning injustices, and that it cares about their problems. Seven years on from the initial #MeToo eruption, the survey data on polarized Gen Z attitudes towards feminism that I introduced earlier suggest that divergence over this suite of issues has become self-sustaining.

As the left leaned into feminism, it also actively antagonized young men. They applied labels like “toxic masculinity” so loosely as to suggest that there is something intrinsically defective about maleness. They also often assumed that gender inequality can run only one way. Yet, as the philosopher David Benatar argues in his book The Second Sexism, there are a variety of inequalities in developed societies that work to the disadvantage of men and boys. Suicide rates among men are much higher. Male infant genital mutilation is legally permitted, unlike the female sort. In some countries, divorce courts tend to favor the mother in child-custody disputes. In others, retirement ages are unequal. Men enter the labor market earlier and on average die younger, but the retirement age for women in rich countries is on average slightly lower. In some places young men are eligible for military conscription whilst women are exempt. This has been particularly divisive in South Korea, where military service for men is universal and notoriously demanding. In Europe conscription is no longer widespread, but Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has increased the salience of the issue for young men in nearby countries such as Poland.

While many on the left barely acknowledge that such problems exist, politicians on the right have been more likely to side with men in cultural conflicts. Donald Trump is an obvious example. His administration revised Title IX rules regarding allegations of sexual assault on college campuses that were regarded as heavily biased against defendants. He criticized MeToo for encouraging false accusations of misconduct against men and boys. Whereas contemporary leftism has acquired a heavily feminized vibe, Trump’s virile personality and enthusiasm for macho events like the Ultimate Fighting Championship have further enhanced his appeal to young men.

The Universities

Unequal rates of participation in higher education probably also play a role in driving gender polarization. People who attend college these days are more likely to absorb a left-wing, egalitarian outlook thanks to the increasingly extreme skew to the left among faculty and administrators. As you can see below, after gender parity was reached in undergraduate admissions around 1980, there has been a steady drift to the distaff side since then. By 2020, female students made up 58% of total undergraduate enrolment in the US and male students just 42%. A similar picture is evident in the EU, where the share of women aged 25 to 34 with degrees rose from 25% to 46% between 2002 and 2020, compared to a rise from 21% to 35% among young men.

It is likely that the feminization of the university system and its “liberalizing” effect on students are now in a causal feedback loop. It is not just that university is making young women more left-wing; women are themselves making the universities more liberal as their share of faculty, staff, and students steadily grows. This reflects the fact that on average men and women on campus have different traits and preferences, with women being somewhat more empathic, egalitarian, conformist, and risk-averse than men. As has been shown elsewhere, this manifests itself in significant disagreements about the point of the university. In survey data, men on campus are more likely to favor free speech, rigor, advancing knowledge, and foundational texts as priorities for higher education, while women are, on average, more likely to prioritize inclusivity, emotional safety, diversity, and social justice. It is not surprising that the female-majority university system that has emerged in recent decades is more left-wing in its institutional culture and priorities than the majority-male one that used to exist.

Female Hypergamy and Lonely Males

The education gap also leads to differences in how men and women experience work and dating. When women graduate from university in a developed country, they are likely to find a white-collar job and be able to support themselves financially. However, when they enter the dating market, heterosexual women find that, because there are now many more female graduates than male ones, the supply of higher-educated men with equivalent salaries and career prospects no longer matches demand. This problem is especially acute given that female romantic strategies are more likely to exhibit hypergamy – in essence, marrying or dating someone you think is more successful and/or financially secure than you.

The dating scene has, in turn, become grim for men who did not go to university. Upwardly mobile women reject them. This, too, has consequences. Research by Off, Charron and Alexander indicates that when men struggle to get ahead, are unable to achieve status, and think public institutions are unfair, they are more likely to resent feminism. It is not difficult to see how these tendencies are increasing the gender gap. For instance, young British men born into areas with high unemployment are more likely to agree with the formula, “Husband should earn, wife stay at home”.

This will be difficult to fix. Hypergamy is probably rooted in evolution, so it’s not going away soon. Disparities between young males and females in the graduate labor market will endure so long as boys are falling behind girls lower down the education system. According to PISA, which tests high school students around the world, 28% of boys but only 18% of girls fail to reach the minimum level of reading proficiency. When these boys grow up and find they are unable to gain social status and are constantly ignored by women on dating apps, they are unlikely to be impressed by a left wing that still sees them as privileged oppressors.

Social Media

As Jonathan Haidt has noted, social media – the lens through which young people increasingly view the world – has probably aggravated polarization as well. Four factors interact here. For starters, Gen Z are far more hooked on phone apps for information and communication than any previous generation, as you can see in the graph below.

Second, social media encourages people to form echo chambers. When groups of like-minded people discuss an issue by themselves, group-think effects, confirmation bias, and out-group shaming kick in. They tend to become more extreme as individuals seek affirmation by reasserting the in-group’s position in increasingly uncompromising terms.

Third, this effect is accentuated by algorithms that amplify sensationalist content. This stokes the grievances of the different camps. Women who click on #MeToo stories will see more of them, as will men who click on stories of men being falsely accused of sexual assault. Each may gain an inflated idea of the injustices that their sex faces, and less exposure to contrary viewpoints.

Finally, “cultural entrepreneurs” shape the ideology of the different online communities in a manner that exacerbates sex polarization. Communities of young women get whipped up over Roe or #MeToo. Among young men, meanwhile, the conversation is often about how to boost self-confidence, gain status, and pick up women, or about the hypocrisies and excesses of feminism. At the edgier end of the spectrum, influencers like Andrew Tate have gained a widespread following expressing “redpill” views that veer towards sexism. As a millionaire partying with attractive women on yachts, Tate embodies an adolescent ideal of masculine success, such that a third of young British men now rate him favourably. The overall effect of all these factors combined has been that young men and women increasingly inhabit different mental universes as a result of the wildly differing content they see on their phones.

The Growing Male/Female Personality Gap

The final major factor driving gender polarization is that sex differences in personality, though consistent worldwide in broadly stereotypical ways, paradoxically tend to widen in more gender-egalitarian cultures. It is not quite clear why sex differences in personality are greater in the West than in Africa and Asia, although one hypothesis is that it is because both sexes become freer to do what comes naturally to them when shorn of the constraints of traditional societies. Regardless of the cause, it has had the effect of increasing the “wokeness gap” between men and women, pushing females towards the identify focused left and away from conservatism.

One psychological difference that has been particularly important in this respect is that women are, on average, more empathetic. Woke ideology is particularly suited to exploiting this, as it presents itself as driven by care for vulnerable groups. Conservatives by contrast are perceived as “mean” and “hateful”. This isn’t an accurate description of conservative ideology, which in reality blends care with considerations of deservingness – tough love, if you like. It also stresses important non-care moral concerns such as loyalty, merit, and freedom. But the growing empathy gap between the sexes means women are less inclined to see these concerns as being valuable. Women are also – again, on average – more egalitarian than males, which in turn increases the appeal of the woke commitment to outcome equality (“equity”) among identity-based groups.

The agreeableness gap is probably also partly responsible for driving young women to the cultural left. This means that, at least when they are being observed by others, men are more likely to hold their ground, act independently, and refuse to conform, whereas women are more likely to conform to the opinions of others in order to prevent social disagreement. Given that social-justice leftism on gender and race has been overwhelmingly favored by elite media and universities over the last decade, it’s unsurprising that it is more appealing to the sex that is more readily swayed by social desirability.

Erik Kaufmann has shown how important the wokeness gap is, in turn, for explaining the growing partisan gap between the sexes. As he points out, “when you control for [woke] opposition to allowing controversial speakers (on BLM, abortion and trans rights) on campus, the statistical effect of gender on ideology collapses … in statistical power.” Further evidence that gender polarization is driven by diffuse cultural grievances is provided by Jan Zilinsky, who has shown that, when it comes to actual policy positions, young women and men don’t differ that much. It is when it comes to self-assigned labels of liberal vs. conservative that the difference becomes much bigger. This suggests that the party labels have become a stand-in for the “cultural progressiveness” gap, which is in turn downstream of these areas of psychological divergence.

In short, what’s driving political gender polarization in Gen Z is not really political at all.

In my next post, I’ll address two other aspects of this issue: What are its social and political consequences? And, to the extent they’re largely undesirable, what if anything can be done to reverse them?

Back in the day,, women looked to husbands to protect them. Today they look to government to protect them..

This is a great piece - timely, well-researched and well thought-out. Speaking for myself, I am reasonably expert in one gender, a perennial student of the other, and when it comes to new "genders" being rolled out, I embrace those changes by covering my head and rolling up into a ball, sucking my thumb and rocking if the opportunity presents itself.

Ayaan lays out so much information that it becomes easy to reach conclusions about the political gender gap. My own take is that some of this is innate - I do agree women are naturally more empathetic than men are. I also believe social media plays a role, especially with younger people, who increasingly descend (it IS a descent-) into their own echo chambers of like-minded individuals for their news and sources of opinion. Some reflects the unusual political hostility of current times, for which Trump has been nothing if not a lightning rod. But I think the overriding causative factor is the exaltation of women in society over the last couple of generations, particularly in academia, and the relative disdain shown towards all things masculine as expressed by our cultural shamans.

More respect and opportunity for women was overdue and I applaud that, but it was done in a way that pushed men down rather than just lifting women up. At the end of the day, it devolved into a culture wide brainwash that - unnecessarily - pitted women against men. The bill for this mismanagement of what could have been a very constructive evolution is now coming due.